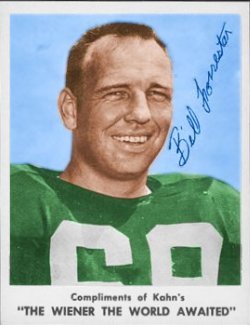

The starting center for Packers in the first Super Bowl had a short career in Green Bay, but that brief time left a lifetime of influence on the man. An articulate speaker and the author of two thoughtful memoirs, Bill Curry spent more seasons, 20, as a head coach than any of Lombardi’s former Packers, although his understanding of the famed coach was much more complicated, questioning, and critical than many of his Green Bay teammates. His coaching success, like that of all his former teammates, was limited, with a cumulative coaching record of 93-128-4.

Curry was selected as a future draft pick in 1964 and then played in the 1965 College All Star Game. He was scheduled to report to Green Bay the day after that game. When the airline could not find his reservation, Bill nearly panicked at the thought of being late for his first practice as a Packer, but had the brilliant thought to invoke the threat of Lombardi’s wrath on the man at the North Central Airlines counter in Chicago should it be his fault that a Packer missed practice. With that, the man chartered a Piper Cub plane to get Curry to Green Bay on time.

Once there, Curry had a personal session with the coach in which Lombardi drew up all of the Packers’ plays on a yellow legal pad and succinctly explained them. Later Ken Bowman would add details and help Curry learn the basics of the position and its responsibilities. In August, he told the Milwaukee Sentinel, “I’m just keeping my stuff in the suitcase in case I’m leaving. I don’t want to leave, of course.” He added, “They ought to call it something else besides football. It’s not like football like I played before. It’s so much quicker. You just don’t have time to fiddle around. Everyone moves so fast. And technique is so important here.”

As a rookie, Curry was a backup at both center and linebacker, snapped the ball on punts and field goals, and played on other kicking and coverage units, too. He also won a ring as a member of the 1965 NFL champions. He returned in 1966 as number two on the depth chart at center, but when Bowman separated his shoulder at the end of the preseason, Bill opened the season as starting center. What’s more, he remained the starter even when Bowman recovered. In December, offensive line coach Ray Wietecha told the Milwaukee Journal, “Curry got his chance because Ken Bowman got hurt. He had to learn all the lessons that Bowman learned the year before. Curry made good progress. But it’s tough breaking in. You could notice his improvement between spring training [sic] and up through about the fourth league game. From then on, it depended a lot on who the opposing middle linebacker was, how good a day he had. That’s always the way.”

Bill started in the NFL Championship against the Cowboys and then the very first Super Bowl against the Chiefs. In the Super Bowl, though, he left early in the second half with a leg injury and was replaced by Bowman. It would be his last game as a Packer; 25 days later on February 9, 1967, Vince Lombardi called Curry to tell him that he had been left unprotected in the New Orleans Saints’ expansion draft and the new team had picked him. Less than a month later on March 6, Curry’s fortunes were reversed again when Don Shula called Bill to tell him he was now a Baltimore Colt, having been included in the deal that sent the Saints’ top draft pick and Curry to the Colts for highly regarded backup quarterback Gary Cuozzo, a second round draft pick and guard Butch Allison. The Colts would select defensive end Bubba Smith with that pick and reap a steal by gaining both two future stars for very little.

Bill would spend the next six seasons in Baltimore, going to two Super Bowls and two Pro Bowls as a Colt. In his first year in the “Charm City,” Curry was a reserve linebacker who got to start a couple of games when starter Ron Porter was injured. The Colts tied for the league’s best record that year at 11-1-2, but missed the playoffs on tiebreakers to the Rams. The Rams then lost in the first round of the postseason to the eventual Super Bowl champion Green Bay Packers in Lombardi’s victorious swan song. Shifted to center in 1968, Curry won the starting job for the ill-fated 13-1 Colt team that lost to Joe Namath’s Jets in Super Bowl III. Along the way, Bill became the media’s go-to-guy for quotes on his former coach. Before a December Colts-Packers game, Curry told the Washington Post, “There’s a lot of individual encouragement among the players on this team. At Green Bay, there was a fear of humiliation in front of your peers.” And then in the January build up to the Super Bowl, Bill contrasted Don Shula’s “enthusiasm” with Lombardi’s terror to the New York Times, “Most of the Packers were afraid of his scoldings and his sarcasm. It’s a form of motivation that works for some people. But it didn’t work for me.”

Curry’s brilliant second memoir, Ten Men You Meet in a Huddle, has perceptive chapters on what he learned from ten very influential people in his football life, including his high school coach, Bobby Dodd, Bart Starr, Willie Davis, Ray Nitschke, Johnny Unitas, Bubba Smith and writer George Plimpton. Perhaps the most interesting, though, are the chapters on Lombardi and Shula, written with the benefit of 40 years of hindsight in which he tries to give each man his due. His chapter on Shula, subtitled “Teacher,” concludes, ”He did it without the distance and aloofness of Bobby Dodd, or the anger and cruelty of Vince Lombardi. To me, Don Shula was the model of what an NFL coach ought to be. He was the best.”

His chapter on Lombardi, subtitled “General,” retells the final meeting of Curry and Lombardi by the coach’s hospital deathbed in which he apologizes for the tone of his remarks to the Times and admits Lombardi meant a lot to his life. Lombardi’s response was, “You can mean a lot to mine if you will pray for me.” Despite his distaste for Lombardi’s methods, Curry ultimately says, “Coach Lombardi forced me against my will to grow up and be a man. He took me places I simply could not have gone without him. I fought him every step of the way, but he was steadfast and confident that his path was the correct path to victory. He was right.”

He continues as a sought-after public speaker, a man with the unique background to discuss the qualities and distinctions of both Bart Starr and Johnny Unitas, as well as Vince Lombardi and Don Shula with passion, humor, and insight.

(Adapted from my chapter in The 1966 Green Bay Packers.)

Custom cards are colorized.