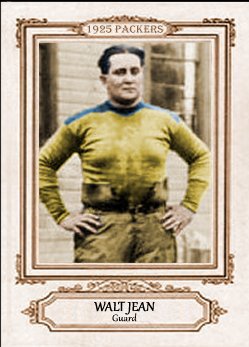

Born Walter Jean in Chillicothe, Ohio on January 12, 1898 was a football lineman of some mystery as to his name, his playing career and his race. According to recent research, Jean was a bi-racial man passing for white in the 1920s when he played for the Packers among other NFL clubs. In 2015, the website “Oldest Living Pro Football Players” noted its U.S. Census research had concluded that Jean had a black father, Marcel, and a white mother, Elizabeth, and was listed as black on the 1900 Census, mulatto in 1910 and 1920, and white in 1930 and 1940.

Packer historian Cliff Christl followed up on that with interviews with family and acquaintances of Jean, as well as tracking down official sources at institutions where Jean was said to have attended. Link The conclusion is that Jean, later referred to as Le Jean and supposedly sometimes as LeJeune, was likely the Packers first black player in 1925, 25 years before Bob Mann, who is commonly given that identifier.

Here is a timeline of Jean’s career, along with some additional post-Packer football affiliations that I have discovered in newspaper research of my own.

1916: Enrolls at Heidleberg University in Tiffin, OH where he is called “Bolo” Jean.

1917: Continues at Heidleberg

1918: In Student Army Training Corps at Heidleberg

1919: Military service

1920: Head coach at Bowling Green University, leading the team to a 1-4 mark.

1921: Finishes college playing eligibility at Bethany College in West Virginia

1922: Plays nine games for the 3-5-2 Akron Pros and scores four touchdowns by playing both in the backfield and line.

1923: Plays five games for the 1-6 Akron Pros.

1924: Plays nine games for the 5-8 Milwaukee Badgers.

1925: Plays nine games for the 8-5 Packers.

1926: Plays 10 games for the 7-3-3 Packers.

1927: Plays two games for the Pottsville Maroons and then joins the semipro Portsmouth Shoe-Steels as player and as the assistant coach to Jim Thorpe. When Thorpe leaves before the season finale, Jean imports former teammates, Red Dunn, Eddie Kotal, Rex Enright and Pid Purdy and coaches the Portsmouth’s 7-6 loss to the Ashland Armcos. Enright and Purdy were injured in car accident and missed the game, however.

1928: Jean continues as the Portsmouth coach for the first two games, with the team now community-owned and going by the name Portsmouth Spartans. After winning the first two games, Jean leaves the team and Keith Molesworth (backs) and Russell Hathaway (line) take over the coaching. Later that season, Jean surfaces playing for the semi-pro Cincinnati National Guards, a rival of Portsmouth.

1929: Jean continues with Cincinnati and is appointed coach on October 22.

1930-32: Jean coaches the semi-pro Dayton Guards.

After this, the 34-year-old appears to leave football. He married in 1935 and worked in various positions while maintaining a winter home in Clermont, Florida and a summer one in Jacksonport, Wisconsin. His wife passed away in 1960, and Jean died on March 28, 1961 from a heart attack at his Wisconsin home.

Custom cards are colorized.