February 23 marks the birthday of two Packer defensive stars: safety Bobby Dillon and defensive tackle Bob Brown.

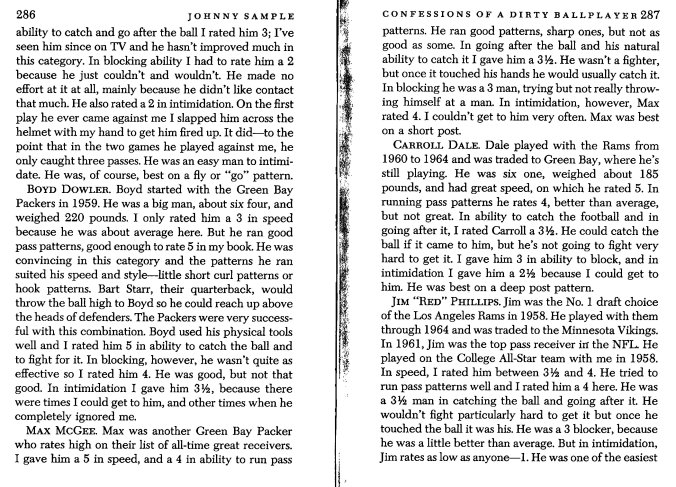

Despite losing his right eye due to two childhood accidents, Bobby Dillon went on to become an All-American at Texas and be drafted in the third round, the 28th overall pick, by the Packers in 1952. Dillon was 6’1” 180 pounds with good speed and unerring instincts. He was a fine tackler, too.

With Green Bay, Dillon played mostly as a wide-ranging centerfielder-type free safety, but switched off to left safety and even cornerback at times because of his ability to stick to receivers. Even though he followed the ball with only one eye, he remains the Packers’ all-time leading interceptor with 52 in just eight seasons. Dillon was also a shifty runner when he grabbed the ball, averaging 18.8 yards per interception return and scoring five times.

From 1953 to 1958, Dillon recorded at least six interceptions in every season and picked off nine balls three times, in 1953, 1955 and 1957. And that was in the era of the 12-game season. In fact, in 1953, Bobby played in just 10 games. While picking off a team record four passes against the Lions that Thanksgiving, Dillon tore ligaments in his knee and missed the last two games of the year.

Dillon teamed with Val Joe Walker, who incidentally had only eight fingers, for a few years to form one of the best safety tandems in the game and was a leader on the defense. In 1957, defensive coach Tom Hearden suffered a stroke, so Coach Lisle Blackbourn appointed Dillon to help out new defensive coach Jack Morton. In 1958, Bobby acted as player-coach of the defensive secondary under Scooter MacLean.

Although Bobby received All-Pro notice seven times and went to four Pro Bowls, he has never received serious consideration for the Hall of Fame, probably due to the fact that he was usually playing on one of the worst defenses in the league. By the time Lombardi arrived in 1959, Dillon was reaching the end. After a lackluster final season, he retired, with Vince saluting him by saying Bobby’s retirement was, “a difficult blow. He is the best in the league.”

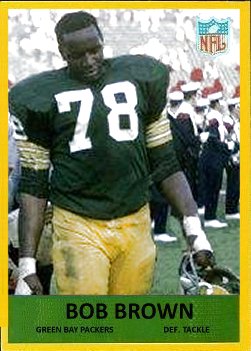

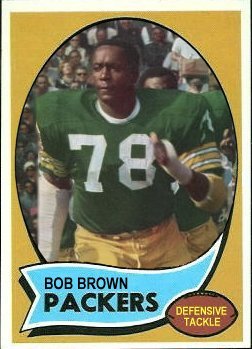

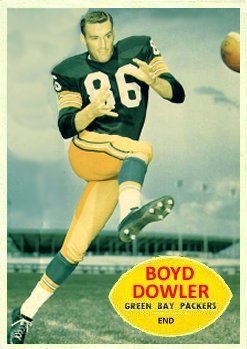

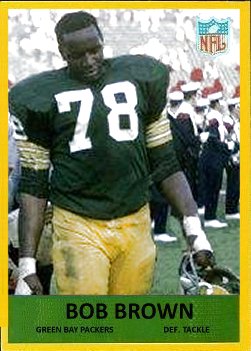

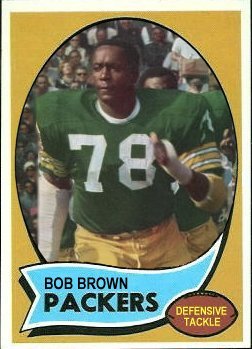

By contrast, Bob Brown took a long, circuitous path in becoming a respected defender in the NFL. Drafted out of Arkansas AM&N in the 13th round of the 1964 draft by San Francisco, Brown tried out for the 49ers in both 1964 and 1965, but was cut both years. In 1964, he played for the semipro Wheeling Ironmen, and in 1965, Bob played for both Toronto in the Canadian League and Wheeling again as well. Personnel man Pat Peppler saw some impressive Wheeling game film of Brown and invited Bob to the Packers 1966 training camp.

Brown was a big man – 6’5” and roughly 280 pounds – who loved to eat, and that probably kept him from reaching his full potential. He often came to camp weighing well over 300 pounds and wouldn’t work himself fully into shape until the season was underway. With size and quickness, he made the defending champions’ roster in 1966 and served as a backup at both defensive end and defensive tackle for his first two seasons. Brown played a vital role in keeping the starters fresh and even recorded a sack in Super Bowl I.

1968 was a lost year for Brown, who broke his arm in training camp and his leg during the season, but in 1969 he became a starter at left defensive tackle, was named the team’s defensive MVP and also led the team in sacks according to Webster and Turney. Bob switched to the right side in 1971 and again was named the team’s top defensive player in 1972. That year, Brown was shot in the neck and had his jaw wired shut prior to training camp, so he reported to Green Bay in fairly good shape. Brown was selected for the Pro Bowl that year as well.

Brown was a powerful interior player. Detroit guard Chuck Walton told reporters in 1973, “He tries to knock your head off 50 times a game. His favorite move is a hard slap at the same time he likes to come in with the other forearm and catch you on the chest from below.” Teammate Jerry Kramer wrote in Distant Replay, “There was nothing cute about the way he played. He was just bull strength coming straight ahead with all he had. He wasn’t going to go around you…He was just going to run the hell over you.”

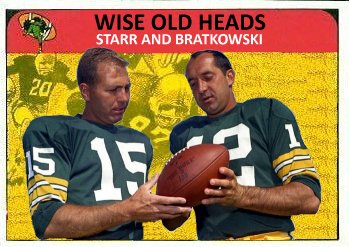

Brown held out in 1974 and was traded to San Diego for a draft pick. He spent two years with the Chargers and two with the Bengals before being cut by Oakland in 1977. In 1978, Bart Starr offered the 38-year old Brown a tryout, but he failed to report.

(Adapted from Green Bay Gold)

Dillon custom cards all colorized.

(Custom card in 1968 Topps style.)

(Custom card in 1968 Topps style.)