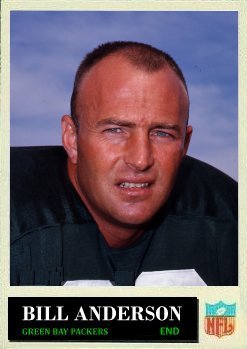

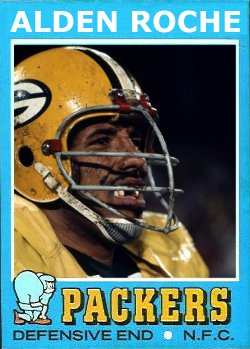

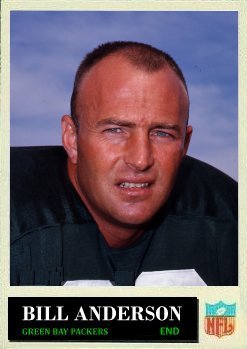

Another of Vince Lombardi’s players passes away a few days ago. Here’s an excerpt of the profile I did on Bill Anderson for The 1966 Green Bay Packers:

Three members of the 1966 Green Bay Packers never appeared in the NFL again after Super Bowl I. Paul Hornung, once the team’s biggest star, was the only player not to play that day for Green Bay. However, little-used veteran journeyman ends Bill Anderson and Red Mack ended their pro football careers that day by playing on the sport’s biggest stage. For Anderson, it was his second straight championship, which was a long way from how his pro career began.

Walter William Anderson was born July 13, 1936 in Hendersonville, North Caolina. He grew up in Onoco, Florida, near Sarasota. He enrolled in the University of Tennessee, where he would play his three varsity seasons under Coach Bowden Wyatt. Anderson was the team’s starting wingback in the single wing offense, averaging 11.4 yards per rush on 29 carries and 23.1 yards per catch on 20 receptions. As a senior, the respected team leader and celebrated defensive back was also co-captain of the squad.

The Washington Redskins, whose coaches worked with Bill in the Senior Bowl, selected him in the third round of the 1958 NFL draft. He would be one of only five of their 30 picks that year who would ever play for the team and the only one who would play more than one full season in Washington.

The 6’3” 210-lb Anderson began his rookie year in the Redskins defensive secondary, but switched to split end in week three. In Washington, Anderson went to the Pro Bowl for both the 1959 and 1960 seasons, catching 35 and 38 passes respectively despite being hampered by a hamstring pull in 1959 and leg problems in 1960. Anderson was switched to tight end in 1961, and at his new position, he caught a career high 40 passes, including 10 for 168 yards in one game against the Cowboys. Nevertheless, Washington’s record was a dismal 1-12-1 in 1961.

At long last the Redskins finally integrated their roster in 1962 by acquiring halfback Bobby Mitchell from Cleveland and moving him to flanker where he caught 72 passes for the improved 5-7-2 Redskins. Anderson shared the tight end job with Steve Junker that year and dropped to 23 catches. The following season, Bill was beaten out by rookie Pat Richter and caught just 14 passes for the sinking 3-11 Skins.

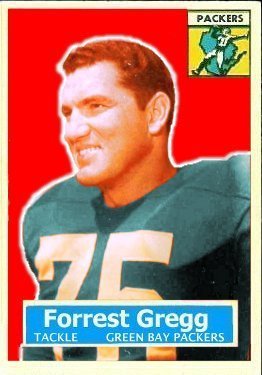

In six years in Washington, Bill had played for three coaches that finished a collective 17-55-6, although his 168 catches in that period were second only to Bones Taylor in team history. However, when his alma mater offered Anderson a position as end coach with the Volunteers, Bill accepted. Also added to the Tennessee staff was Forrest Gregg who retired for the first time from the Packers. Gregg had played under Doug Dickey in service ball, but was talked into returning to Green Bay just two months later by Vince Lombardi.

After one season as a coach, though, Anderson returned to Washington to restart his playing career. He told the Washington Post he retired because, “I was tired of getting banged around every Sunday.” After a year on the sidelines, his feelings changed, “I really want to play now. I didn’t know I had it so good. Coaching makes you appreciate being able to play.” Returning to the Redskins, he found a logjam at tight end. Since Green Bay had lost starting tight end Ron Kramer to the Lions, Vince Lombardi was looking for veteran insurance behind new starter Marv Fleming, so he gave Washington a sixth round pick for Anderson on August 18, 1965. Bill later told the St. Petersburg Times, “My first reaction was one of disappointment at being traded. After all, I had made quite a few friends in Washington, and here I had to almost start over again. Yet, I had an idea I might be traded. As it turned out, it was the greatest thing that could have happened to me.”

Anderson was brought in as a backup and as the edge man on the kickoff coverage. He spent most of the 1965 season in that capacity, catching just eight passes all year. His seasonal highlight came in week 12 when Bill caught a 27-yard touchdown for the winning score in a 24-19 triumph over the Vikings. Although having some back problems, Anderson began to be used more late in the year due to Fleming’s sore ankle and lackadaisical play. After the Minnesota game, Lombardi beamed, “Anderson was worth his whole year’s salary in that one game last week.”

The 1965 season concluded with the Packers and Colts tied for the lead of the Western Conference, necessitating a playoff game between the two on December 26, 1965 in Lambeau Field. The Colts were under the handicap of having lost both starting quarterback Johnny Unitas and backup Gary Cuozzo to injuries and were relying on halfback Tom Matte to run the offense. The first play from scrimmage evened things up a bit between the two clubs. Bart Starr connected with Anderson on a pass play, but when rocked by defensive back Lenny Lyles, Bill fumbled. Colt linebacker Don Shinnick scooped up the ball and returned it for a touchdown, with Starr cracking his ribs in the melee at the goal line. He explained to the St. Petersburg Times, “What happened was that the ball hit me in the shoulder, instead of the stomach. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a defender coming in to hit me, and I was trying to get the ball down into my stomach in time. I didn’t quite make it,” Bill recalled and added, “If there was a tunnel handy, I’d have crawled into it and run out of the stadium and kept on running.”

Ironically, had the play occurred today, it most likely would have been ruled incomplete since Anderson was unable to complete a “football move” after grabbing the ball. In addition, during the scramble for the loose ball, Anderson was hit in the head and suffered a concussion, “It was all a little hazy the rest of the way,” he later noted.

Hazy or not, Anderson proceeded to have the game of his life, catching seven more passes from backup quarterback Zeke Bratkowski to lead the team in receptions. Often, he slipped into the middle of the field vacated by blitzing middle linebacker Dennis Gaubatz to give Bratkowski an outlet. Bill’s last catch came late in the overtime period and went for 18 yards to move the ball close to midfield; eight plays later, Don Chandler kicked the game-winning field goal. Chandler’s first field goal had tied the game in the last two minutes and remains controversial to this day. Whenever anyone questioned Anderson whether that field goal went through the uprights, though, Bill would hold up his hand and reply matter-of-factly, “I’m wearing a dang ring.”

One week later, a bruised Starr returned for the NFL Championship against the defending champion Browns, held again in Lambeau. Bill again started, but served primarily as a blocker. Starr told the Milwaukee Sentinel, “Early in the game, I was trying to hit Anderson but in the pass coverage Cleveland was using, it was awfully tough to throw to the tight end. They were holding up Anderson at the line of scrimmage.” Bill caught no passes that day, but Green Bay won handily 23-12 for Lombardi’s third title and Anderson’s “dang ring.”

Bill returned to the Packers for 1966. By opening day, though, he was again backing up Fleming. Anderson got into 10 games in 1966 and caught just two passes, including one during the game-winning drive in the opener. Despite his diminished role on the Super Bowl-winning Packers, Bill was invited back by Vince Lombardi for 1967, but decided to get on with his life’s work. A year later, he was paired with play-by-play announcer John Ward to broadcast Tennessee football games. Bill would be Ward’ color analyst for the next 31 years, and the two would retire together following the 1998 season; their final broadcast was the Fiesta Bowl on January 4, 1999 when Tennessee beat Florida State 23-16 to win the National Championship, a fitting conclusion to the longest running broadcasting partnership in college football. The two were somewhat analogous to the Packers 20-year broadcasting pair of Jim Irwin and Anderson’s former teammate Max McGee who ended their run just one day earlier on January 3, 1999.

Custom cards in Philadelphia style.