Today in 1932, Lew Carpenter was born in Hayti, Missouri. After graduating from West Memphis High School, he enrolled at the University of Arkansas in 1949. Carpenter showed an early propensity for flexibility for the Razorbacks by appearing at halfback, fullback, end and quarterback in his three years on the varsity, where of his teammates was future Packer Dave Hanner.

Carpenter was drafted in the eighth round in 1953 by the defending NFL champion Lions and was part of the Lions second consecutive championship run as a rookie. He spent four seasons in Detroit, primarily as a halfback on offense, leading the team in rushing in 1954 and ’55, but he also played on defense. In his first ever game in 1953, he returned an interception 73 yards for a touchdown.

After a year in the military, Lew was dealt to the Browns in 1957 for former Packer linebacker Roger Zatkoff. In Cleveland, he teamed with his younger brother Preston who played end for the Browns. After two seasons in Ohio, Carpenter was traded to Green Bay as part of a deal that sent end Bill Howton to Cleveland for Lew and defensive end Bill Quinlan. At the time, Lombardi praised him as a steady player who could help keep the offense moving.

Carpenter was third on the team in rushing in 1959 with 322 yards, but would gain only 37 more yards rushing in his remaining four years as a Packer. Instead, he was Vince Lombardi’s eager utility man, playing both as a runner and receiver as well as returning punts and kicks and playing on the kicking teams. In Run to Daylight, Lombardi says, “Lew Carpenter, whose younger brother Preston is with the Steelers, is in his ninth year, but no first year man works harder from July into December than Lew…It is the older ones, like Lew Carpenter and Gary Knafelc and Johnny Symank, who still give you everything they’ve got and who have my deepest admiration. They keep you alive when you are hurt and in pain and would otherwise be dying in some game.”

Following the 1963 season, Carpenter retired to take a coaching position with Norm Van Brocklin’s staff in Minnesota. He would coach receivers and tight ends in the NFL for the next 30 years for the Vikings, Falcons, Redskins (under Lombardi), Cardinals, Oilers, Packers, Lions and Eagles. In Forrest Gregg’s third season as head coach in Green Bay, he replaced Lew as receivers coach with young Tom Coughlin, even though Carpenter was still under contract for 1986. That rejection stung, but Lew moved on to Detroit the following season. He finished his coaching career with Southwest Texas State in 1995 and the Frankfurt Galaxy of the World Football League in ’96.

Although he never coached for a championship team, Carpenter appeared in six NFL title games in his ten seasons as a player (1953, ’54, ’57, ‘60, ’61 and ’62) and won three rings–one with Detroit and two with Green Bay. He died on November 14, 2010 in New Braunfels, Texas, and after his death, it was determined that Lew had suffered from CTE, which explained his erratic behavior in later years.

Carpenter was survived by his wife and four daughters. Youngest daughter Rebecca, who had long worked in the film and television industry, spent four years putting together a 90-minute documentary about her father and CTE entitled, Requiem for a Running Back. It premiered in 2017 and has drawn favorable reviews.

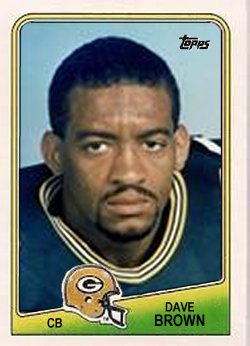

All custom cards but 1961 are colorized.