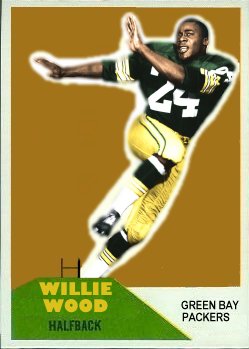

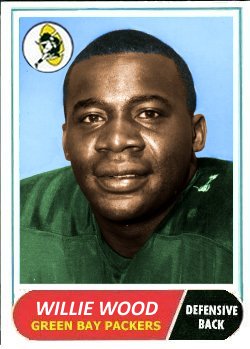

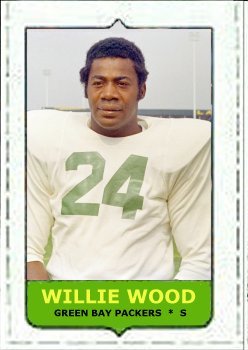

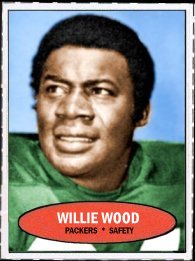

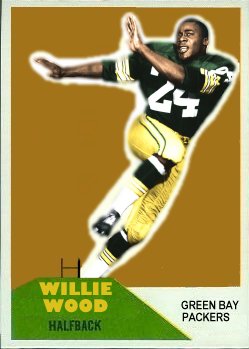

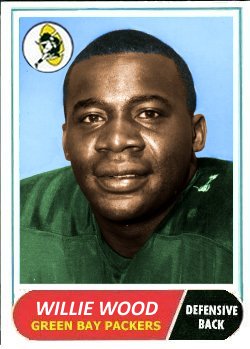

Lombardi’s Packers continue to hear the inevitable final gun. Willie passed away last week, and he will not be forgotten. Wood grew up in Washington D.C. and went west to go to college, starting at Coalinga Junior College before ending up at the University of Southern California. At USC, Wood was a three-year letterman as a 5’10” running quarterback. His position coach was Al Davis, future owner of the Raiders. Wood broke his collarbone as a senior, and that was the third strike against the injured, undersized, black quarterback who went unclaimed in the 1960 NFL draft. He and his high school coach Bill Butler started writing letters to professional teams requesting a tryout, but received no response until Jack Vainisi and Vince Lombardi of the Packers decided to give him a look. Given a chance, he made the Packers in 1960, and it was his good fortune for two reasons. Not only had he gotten in on the ground floor of the Green Bay glory years, but he got to spend two years with one-time free agent Emlen Tunnell who was winding down his career in Wisconsin. Tunnell, who had been the premier safety in the league throughout the 1950s and would be the first black player inducted in the Hall of Fame, was a generous individual who became both roommate and mentor to Wood. Willie would later say, “Em taught me everything”

Although Wood was listed as the team’s third quarterback after Joe Francis broke his leg, Willie made a strong impression in practice when he laid out Jim Taylor with a solid tackle. Lombardi ordered the play run again, and Wood dropped the larger Taylor again. Lombardi and the whole team were impressed with this little man’s toughness. His first appearance on defense came in the sixth game of the 1960 season against Johnny Unitas and the Colts. Starter Jesse Whittenton got hurt, so Willie was inserted at left cornerback against All-Pro receiver Raymond Berry. Wood repeatedly was beaten and eventually was replaced that day by Dick Pesonen. After the game, Wood was badly shaken and uncertain about his future when Lombardi took him aside and told him to shake it off because he was going to be here as long as the coach was. The coach had good reasons to have confidence in Willie Wood. Although he was not extremely fast, he was very quick and a great leaper–he could dunk a basketball and played pickup hoop games against NBA star Elgin Baylor back in DC. Wood was said to be able to touch the crossbar of the goal posts with his elbow. Beyond that, he was a smart player and became the surest tackler on the team.

In 1961, Willie won the starting free safety position replacing the aging Tunnell, and the Packers won their first title in 17 years. Shades of his mentor, he intercepted five passes and led the league in punt returns with a 16.1 average return. Two punts he took back for touchdowns. The next year, he led the NFL in interceptions with nine and averaged 11.9 yards per punt return. He also kicked off for the team. Oddly, he was ejected from the 1962 title game when he jumped up quickly to protest a penalty call and accidentally bumped into the official.

The most memorable moment of his career came in the first Super Bowl when he intercepted a Len Dawson pass early in the third quarter and returned it 50 yards to the Kansas City five. Elijah Pitts scored on the next play, and the game was essentially over. His teammates ragged Wood for being run down from behind by fellow USC alumnus Mike Garrett, but Willie was never known for his speed. Willie still is the all-time team leader in most punt returns (187) and most fair catches (102), but after his first five years he wasn’t very effective at it. His punt return averages in those first five years were 6.6, 16.1, 11.9, 8.9, and 13.3. After that, he never averaged more than 5.3, and his overall average for the last seven years was a pitiful 3.8.

As his punt return talents dwindled, though, his safety skills became more highly respected. Wood was named All-Pro for the first of six consecutive seasons in 1964. In that same year, he was named to the first of eight straight Pro Bowls. While he never approached Tunnell’s 79 lifetime interceptions, Willie trails only newly-minted Hall of Famer Bobby Dillon with 48 in 12 years as a Packer, and he returned two picks for touchdowns.

The Packers’ greatest free agent, Willie Wood, had the full respect of his teammates. Fiery Ray Nitschke said, “I hate to miss a tackle because I know if I do, I’m going to get a dirty look from Willie. He’ll kill you with that look.” Wood was a leader on a defense of stars so it was not surprising that he went into coaching after retiring as a player after the 1971 season. He served two years as the defensive backs coach in San Diego before becoming the first black head coach of a professional football team with the Philadelphia Bell in the World Football League in 1975. The Bell had a losing record that year before the entire league folded. Willie got a second chance in the Canadian Football League when he took over the Toronto Argonauts from his former teammate Forrest Gregg in 1980. The talent-poor Argos went 6-20 over the next two seasons and Wood was fired. Wood left football for business at that point and moved back to his hometown of DC. He was elected to the Packer Hall of Fame in 1977, and his long-overdue induction to Canton occurred in 1989. Sadly, the last dozen years of this hard-hitting defender’s life were marred by a steadily darkening fog of dementia and were spent in an assisted living facility. He was 83 and is survived by three children.

(Adapted from Packers by the Numbers)

Custom cards 1,2,5 and 8 are colorized.