The third installment…

All custom cards are colorized.

The third installment…

All custom cards are colorized.

Here’s an excerpt from my new book that talks about the coaching style of Curly Lambeau:

The basis for Lambeau’s offense was the Notre Dame Shift he learned in his one season under Knute Rockne. The offense would line up in a T formation with a balanced line, a guard, tackle and end on both sides of the center. On signal, the backs would shift into a box that resembled a single wing backfield, and the ends might flex out a bit from the tackles. In the box, the left halfback, fullback and quarterback shifted laterally, while the right halfback moved toward the line and to the right, lining up as a slot or wingback. The shift could go either to the right or to the left.

From that basis, Lambeau’s attack varied, depending on the talent he had on hand. In the early Twenties, he was the main back and would receive a deep snap from the center in the halfback position. Charlie Mathys, the 5’7” Packer quarterback was more of a receiver and blocker who caught a league-leading 33 passes in 1923 and topped the NFL again in 1924 with 30 catches. With the coming of Verne Lewellen and other talented backs in the mid-Twenties, the offense grew more diverse, with more backs taking snaps. When Lambeau obtained Red Dunn at quarterback, though, his offense took into account what Dunn offered. Dunn was best at taking a short pass from center and distributing the ball, whether on a handoff to another back or via a pass. The quarterback did not always get the ball, but that exchange was much more prevalent with Dunn at the position. This version of the offense was sometimes referred to as a V formation because that’s how the quarterback, left halfback and fullback aligned, and this offense, which was attuned for quick opening plays, bore some similarities to a more modern T formation.

After Dunn retired, though, Arnie Herber did not have the skill set to run that offense, nor did he possess the running ability that a traditional single wing tailback would have. What he did best was throw the ball deep, so that was his main function in the 1930s. Lambeau accumulated a host of multitalented backs to fit into his versatile 1930s attack: Clarke Hinkle, Bob Monnett, Joe Laws, Hank Bruder and eventually Cecil Isbell — who did have the triple threat skill set of the ideal single wing tailback. Watching film of the Packers of the late 1930s and early 1940s, one sees backs moving between different positions and substituting fairly regularly. It should also be noted that Green Bay usually had one of the better placekicking units in the NFL, finishing first or second in the league in field goals nine times between 1934 and 1947. Going back to the acclaimed punting of Verne Lewellen, Lambeau placed emphasis on the kicking game.

And then there was Hutson. Jimmy Conzelman claimed, “Hutson is the only football player who ever lived who forced an opposing coach to put two men against him.” Jimmy saw Don’s qualities as, “four-fold: speed…hands…judgment of a thrown ball…his big act.” That “big act” alludes to the pass patterns that Hutson frequently is credited with creating. Cleveland sportswriter John Dietrich memorably characterized the 1930s Packer attack as, “The Packers, shooting passes in all directions from their gyrating Notre Dame offensive, were the most air-minded outfit to pester Cleveland this year.” Charting nine game films from the 1940s provides additional insight to the air attack. In those games, Hutson flexed out at least a few yards on 67% of offensive plays, while other Packer ends did so just 17% of the time. By contrast in the 1939 title game, Hutson was flexed less than one third of the time. In support of this thought, Clarke Hinkle told Murray Olderman that in the 1930s, “The offensive formations of our day spanned about 12 yards because we did not have flankers and split ends. In addition, our offensive linemen were not spaced as loose. Result: the defensive formations were tighter, so it was harder to find a hole.” Although it’s an extremely small sample, the film I’ve seen makes me wonder whether the positioning of Hutson on offense evolved over time.

On defense, his positioning distinctly changed when Lambeau brought in bruising Larry Craig as quarterback in 1939. Quarterback in that offense solely meant blocking back. Craig functioned like a fullback in more contemporary offenses; he was purely a lead blocker. His talent allowed Lambeau to make a major move to preserve the health of his greatest player. Instead of having Hutson line up at defensive end, Craig took that slot, while the ball-hawking Hutson became the team’s leading interceptor in the secondary. This move was very unique at the time. Two-way players did not shift around so freely. To Lambeau’s credit, he was considering it as early as 1936 and did not hesitate to make the move when he got the right player to make it work in 1939.

Lambeau claimed to be one of the first to move from a seven- to a six-man line in the 1930s, with the center dropping back to join the fullback as a second linebacker. Generally, his teams had strong defenses. His most famous strategic defensive move, though, came in 1941 when he switched the Packers back to a seven-man line to upend the mighty Chicago offense and beat Bears 16-14. Unfortunately, in the playoff at the end of the season, the strategic magic wore off, and the Bears crushed the Packers 33-14. Perhaps what was really missing at that point was superstar linemen of the caliber of Cal Hubbard and Mike Michalske from the 1929-1931 champions.

Not everyone thought highly of Curly’s strategic acumen. Cal Hubbard told Ralph Hickok, “Hell, sometimes Curly would design a new play, draw it up on the blackboard, and we just knew it wouldn’t work the way he drew it. He’d have impossible blocking assignments, or the play would take too long to develop. The defense would mess it up before it got going. We’d have to tell him that, and one of the veterans would go right up to the blackboard and change it around. Most of the time, Johnny Blood was the spokesman because he was always ready to speak up to Curly.” Mike Michalske partially agreed with Hubbard but added, “He really learned football from his players, and after a few years I think he knew as much as any coach in the game.” Don Hutson, who came along a little later, felt differently, “I was fortunate in having a creative coach like Curly Lambeau, one who really saw the merits of the passing game at a time when just about no one else did.”

And then there was his manner. An article in the Milwaukee Journal the day after the Packers won the 1936 championship was titled “Curley [sic] Spouts Advice; Nobody Pays Attention,” and bemusedly depicts Lambeau’s vocal antics on the sidelines during the game with the emphasis on the players disregarding him. Guard John Biola remembered, “And how he would rant and rave. During a game, nobody would want to talk to him. You’d stay as far away as you could on the bench.” Clarke Hinkle stated, “I never really liked him. Didn’t really respect him either.” Hinkle did consider Lambeau a “great psychologist” though. Center Charley Brock thought, “Curly never became too intimate with the players, and as the years progressed we realized it was because he didn’t want to lose control of them.” Guard Buckets Goldenberg asserted, “He was a great salesman. He could sell oysters to a fisherman. It was this salesmanship that helped him develop so many stars.” Bob Snyder, an assistant coach at the end of Lambeau’s tenure in Green Bay, told Cliff Christl, “I don’t think players played out of respect for Curly as much as out of fear of Curly.”

By the late 1940s, the talent was gone and Lambeau was out of ideas. He shifted the offense to the T in 1947 and imported a passer, Jack Jacobs, to run it. After one more mediocre season everything fell apart. In 1948, he completely lost the team when he fined each player a full game check after they lost for the second time in week four. Once the team beat a tough Rams squad in week five to pull to 3-2, though, Lambeau infuriated the team by not rescinding the ridiculous fine from the previous week. He lost all authority and went 2-17 in his last 19 games in Green Bay. Today we remember Lambeau for his glory days when he championed the passing game and led six teams to championships. Curly once told sportswriter Ollie Keuchle that his most satisfying game was the 1940 College All-Star Game when the 1939 champs dismantled the college boys 45-28 and displayed the awesome power of the air game, “We scored more points than the pros had scored in the six previous games combined and opened the eyes of those who for so long had refused to accept pro ball for what it was.” It was his passing attack that brought that acceptance.

All custom cards colorized.

86 was first worn in Green Bay by linebacker Bill Schroll in1951. Since then, it has been worn by seven wide receivers and nine tight ends.

WR: Bill Howton (1952-58), Boyd Dowler (1959-69), Kent Gaydos (1975), Jessie Green (1976), Antonio Freeman (1995-2001, 2003), Chris Jackson (2002) and A.J. Moses (2002).

TE: John Hilton (1970), Pete Lammons (1972), Mike Donohoe (1973-74), Ed West (1984-94), Don Summers (1987r), Donald Lee (2005-10), Brandon Bostick (2013-14), Kennard Backman (2015) and Emanuel Boyd (2017).

The transition from one Packer hall of famer (Howton) to another (Dowler) was seamless in 1959. Dowler and tight end Ed West wore the number the longest (11 years), while the longest gap that the number was not worn was from 1977-83. Antonio Freeman, another member of the team’s hall, also should be noted as a star in 86.

First four custom cards are colorized.

The second installment of the Topps 1955 Packers team set…

All but the first custom card are colorized.

Four Packers share July 21 as their birthday. Former Minnesota Gopher tackle Lou Midler was the first. He appeared in seven games for the 1940 Pack.

Defensive back Dale Hackbart turns 81. He was drafted out of Wisconsin in the fifth round by Vince Lombardi in 1960 and was a reserve on the Western Conference champs that season. In 1961, Lombardi dealt Hackbart to the Redskins for a sixth round pick in week three. The pick was later used to select John Sutro. Hackbart went on to have a 12-year NFL career with Washington, Minnesota, St. Louis and Denver before broken bones in his neck ended his career in 1973. He also played minor league baseball and pro football in Canada.

Center Bob Hyland turns 74. He was the ninth overall pick in the 1967 draft out of Boston College and had an 11-year NFL career with the Packers, Bears, Giants and Patriots. Hyland won a Super Bowl ring as a rookie but was unable to dislodge Ken Bowman from the starting lineup in three years and was included in a trade that sent him, Elijah Pitts and Lee Roy Caffey to Chicago for the second overall pick in 1970 that netted Green Bay Mike McCoy. A year later, Hyland was with the Giants and on opening day in Lambeau Field plowed into new Packer coach Dan Devine and broke the coach’s leg. He was reacquired the week before the 1976 season after the Giants cut him and spent one more season in Green Bay before being cut in August 1977. A lifelong Resident of White Plains, NY, Hyland ran his own sports bar there for over 30 years and even ran for town mayor in 2011.

Safety Jim Hill was a first round draft pick of the Chargers in 1968 and spent three seasons in San Diego before Dan Devine acquired him for Lionel Aldridge and a third round pick in 1972. Hill and rookie Willie Buchanon turned the Packer secondary into a strength and a contributing factor to the team’s divisional championship that year. He spent three years in Green Bay before finishing his NFL career in Cleveland in 1975. Since then he has been a highly respected sportscaster and community leader in Los Angeles, even earning a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and having May 9, 2006 declared “Jim Hill Day” in Los Angeles. His brother David played tight end for the Lions and Rams for 12 seasons. Jim turns 73 today.

First custom card is colorized.

Update: This Jim Hill was actually born on October 21. The Jim Hill that was born on July 21 was a defensive back who played for the Lions from 1951-52 and the Steelers in 1955. I regret my confusion here.

Today two former Packer guards celebrate birthdays. Dave Drechsler turns 59 and Randy Winkler hits 75. Drechsler was Green Bay’s second round draft pick in 1983 and started as a rookie. In 1984, he ruptured discs in his back during training camp, but still began the season in the starting lineup. In week three, though, new coach Forrest Gregg replaced both his guards (Drechsler and Syd Kitson) in search of more bulk and aggression from new starters Tim Huffman and Ron Hallstrom. Drechsler was cut the following training camp.

Winkler arrived with less fanfare. A 12th round pick out of Tarleton State by the Lions in 1966, Randy played for Detroit in 1967 and Atlanta in 1968 before being called up by the Naval Reserves. He spent the 1969 and ’70 seasons coaching the offensive line for the Naval Academy until returning to Atlanta in 1971. The Falcons cut the rusty Winkler in August, and the Packers signed him to their taxi squad. He appeared in five games for Green Bay that year and was waived during training camp the following year.

Custom cards are colorized.

Tackle Don Deeks was the first to wear 85 for the Packers in 1948 and he was followed by tackle Joe Ethridge in 1949 and center Jay Rhodemyre in 1951. Since then, it has been worn by three ends, one defensive back, 16 wide receivers and four tight ends.

E: Ab Wimberly (1951), Jim Jennings (1955) and Emery Barnes (1956).

DB: Al Romine (1955).

WR: Max McGee (1954, 1957-67), John Spilis (1969-71), Dick Gordon (1973), Ken Payne (1974-77), Elmo Boyd (1978), Bobby Kimball (1979-80), Phil Epps (1982-88), Lee Morris (1987r), Jeff Query (1989-91), Kitrick Taylor (1992), Ron Lewis (1992-94), Terry Mickens (1995-97), Corey Bradford (1998-2001), Karsten Bailey (2002-03), Terrnece Murphy (2005) and Greg Jennings (2006-12).

TE: Wesley Walls (2003), Sean McHugh (2004), Jake Stoneburner (2013) and Marcedes Lewis (2018).

McGee wore the number longest (12 years) and with the most distinction; he is the only 85 to be a member of the team’s hall of fame, but he will likely be joined at some point by Greg Jennings. The only multiple year gap when the number was not worn was from 2014-17.

First two custom cards are colorized.

Big Leon Crenshaw was born on July 14, 1943. The Alabama native graduated from Tuskegee Institute and spent five years trying to get a foothold in the NFL. Failing trials with the Cowboys, Patriots and Packers, he played for the minor league Rhode Island Indians in 1965 and the Lowell Giants in 1966-67,

The 6’6” Leon reported to Vince Lombardi’s last training camp in 1967 at 315 pounds, and his struggles to drop weight are detailed in Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay. The July 19 entry notes, “…big Leon Crenshaw could barely stand up. His legs were wobbling, his tongue was hanging out, he was just about to fall down when we’d stop and rest a few seconds and then we’d go again.”

A day later, Kramer reports, “…standing in line waiting for his food, Leon Crenshaw crumpled up and passed out and lay on the floor groaning. We threw an ice pack on him and tried to cool him off a little bit, but we couldn’t move him. He couldn’t even sit up. Finally, someone called an ambulance, and they hauled Leon off to the hospital. He was totally dehydrated, totally exhausted. He’s lost twenty-five pounds since he’s been in training camp.” He was back to grass drills and wind sprints the next day after four to five hours of intravenous fluid at the hospital but was waived on September 11, a week before the season.

Back he came in 1968, though, and made the team at 278 pounds. Coach Dave Hanner told Lee Remmel in September, “He gives you 110 percent on every play…I have a lot of confidence in him.” Crenshaw commented, “Every move I make, Coach Hanner tells me what I’m doing wrong. What he is saying helps me understand my own moves.”

Crenshaw appeared in 10 game for the Packers that year, but the next year bounced from the Packers to the Falcons to Vince Lombardi’s Redskins during training camp before finally having surgery on his ankle. With the end of his career, he eventually went into the ministry and died at age 65 on August 22, 2008.

First two custom cards are colorized.

I have a new book coming out in the coming weeks in which I examine the influence of coaches from the first 30 years of the NFL on the evolution of the game and league: Pioneer Coaches of the NFL: Shaping the Game in the Days of Leather Helmets and 60-Minute Men. Here’s an excerpt from the start of chapter 2 called, “Taking Flight: Curly Lambeau and LeRoy Andrew Work the Passing Game.”

As already established, pro football in the 1920s was a tough slog. Opponents generally were mirror images of each other: a single-wing power ground attack on offense and the ubiquitous 7-1-2-1, or “seven diamond,” defense. Most teams were led by a player-coach who adhered to the simple dictates of “straight football” to keep hitting the opposing line until it broke. Two player-coaches went against the grain, though, and strove to open up the game with the aerial attack. Curly Lambeau in Green Bay and LeRoy Andrew in Cleveland, Detroit and New York followed their own paths to find a better way to win football games.

Analyzing the unofficial and incomplete league statistics for the period from 1920-31 compiled from contemporary game accounts by Neft, Cohen and Korch, it is clear who the dominant passing teams were. Lambeau’s Packers led the league in passing yards four times (1923, 1924, 1926 and 1931), finished second four other seasons, third once and fourth once. Andrew coached for only seven full seasons, but his team finished first in the league in passing yards the last four of them and led the league in points each of those years. It should also be noted that teams coached by Chapter One’s Guy Chamberlin twice led the league in the period and finished second once and third once. Passing was difficult and erratic but the better teams demonstrated its value.

Lambeau and Andrew were the two coaches most devoted to the air game, but were drawn to it for different reasons. For Curly, it was a more natural inclination in that the Packers’ player-coach was the original passing star for the team as its tailback. He passed the ball because he liked to play that way and saw its potential for creating a winner. He told sportswriter Lee Remmel, “I always loved to pass. I used to practice passing in the spring. The ball was harder to throw then – it was bigger around.” He added, “I don’t think we would have gotten into the National Football League without passing. We took advantage of the defense, and it paid off.”

LeRoy Andrew also began as a player-coach but usually played in the line. At his first NFL coaching stop in Kansas City (with the Blues in 1924 and the Cowboys in 1925-1926) he did not have a strong passing attack. However, Andrew jumped at the chance to sign Benny Friedman, the best passer in college football, once the franchise moved to Cleveland in 1927 and gladly let Friedman air it out on offense. LeRoy was flexible enough to change his approach to accommodate the special talents of his best player, and he stuck with Friedman and the passing attack as they moved from Cleveland to Detroit to New York.

In addition to their shared proclivity for the pass, the other striking similarity between these two coaches is that they both started teams and had to find financial sponsors or backers to enact their gridiron dreams. Lambeau found his initial backing from his employer, the Indian Packing Company. Later, the team was supported by a handful of Green Bay’s leading citizens who set up public ownership of the franchise. Andrew was the driving force to establish pro football in Kansas City and found investors for the new team, too. He then was instrumental in the subsequent sale of the franchise and players to Cleveland and then Detroit and finally to New York. For both coaches, this led to them operating their teams with a great deal of independence and ensuring things unfolded the way they envisioned. Andrew’s nearly-complete franchise control ended once he joined Tim Mara’s Giants, and that would lead to his ouster. By contrast, Lambeau enjoyed autonomy in running the community-owned Packers for a much longer period and had a more extended sad denouement to his celebrated coaching career.

Custom cars are colorized.

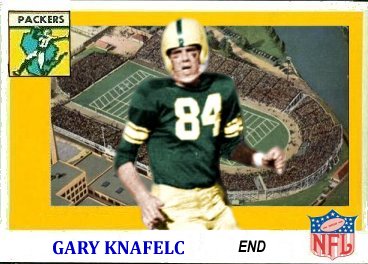

84 was first worn in Green Bay by two-way end Don Wells in 1946. After a six-year gap, offensive end Gary Knafelc next wore it in 1952. Since then, it has been worn by 12 wide receivers and three tight ends and there have been four two-year gaps when it was not worn (1963-64, 1982-83, 2009-10 and 2013-14).

E: Don Wells (1946) and Gary Knafelc (1954-62).

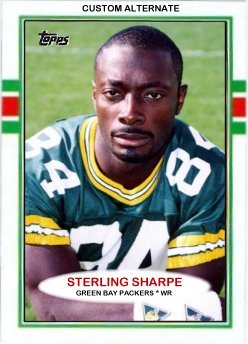

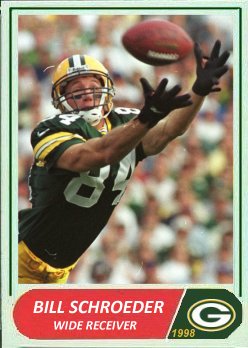

WR: Carroll Dale (1965-72), Steve Odom (1974-79), Fred Nixon (1980-81), Lenny Taylor (1984), Nolan Franz (1986), Wes Smith (1987r), Sterling Sharpe (1988-94), Anthony Morgan (1996), Andre Rison (1996), Bill Schroeder (1997-2001), Javon Walker (2002-05) and Jared Abrederis (2015-16).

TE: Tory Humphrey (2006, 2008), D.J. Williams (2011-12) and Lance Kendricks (2017-18).

Knafelc wore it the longest at nine years, but Carroll Dale wore it for eight and Sterling Sharpe for seven. All three are members of the team’s hall of fame. Sharpe belongs in Canton.

First two custom cards are colorized.